Length: SVL: Males up to 31mm; Females up to 40mm

Weight: Up to 5 grams

Description

Archey's frog is New Zealand's smallest, and perhaps most beautiful native frog species. It is distinctive in both its terrestrial lifestyle and its archaic form, belonging to one of the most ancient lineages of amphibians on the planet.

They are perfectly adapted to their forest environments with their dorsal (upper) surfaces matching the surrounding vegetation. Typically they are light to dark brown, green-brown, or green with dark brown or black blotches and occasionally brilliant green mottling. Dorsolateral lumps (glandular ridges) are present on the dorsal and dorsolateral surfaces. Their lateral surfaces (sides) are brown, pinkish, or orange-brown with black blotches, flecks, and sometimes green mottling. Similar markings can be seen on the arms and legs of this species, with the legs often bearing distinct dark or green transverse bands. Occasionally, the lower lateral surfaces and upper limbs bear brilliant orange or even pale blue colouration. Black markings are typically present under the eyes and upper lip. Ventral (lower) surfaces are typically black or dark brown and may be mottled with green, pale blue, or yellow. Eye colour black with a light golden or golden-brown upper portion. Feet are unwebbed with thin toes, due in large part to their terrestrial nature. As with other Leiopelma, Archey's frogs show slight sexual dimorphism, with females being larger than males (van Winkel et al. 2018).

Archey’s frogs are similar in appearance to our other native frog species but can be differentiated by a combination of their smaller size, terrestrial nature, often brilliant colouration, and lack of webbing on the hindlimb. They co-occur with the semi-aquatic Hochstetter's frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri) on the Coromandel Peninsula, and in the King Country, but are much smaller, and lack webbing.

Life expectancy

Like our other endemic frog species, Archey's frogs are extremely long-lived, with the age records of males and females being 33 years, and 39 years, respectively (Bell et al., 2023).

Distribution

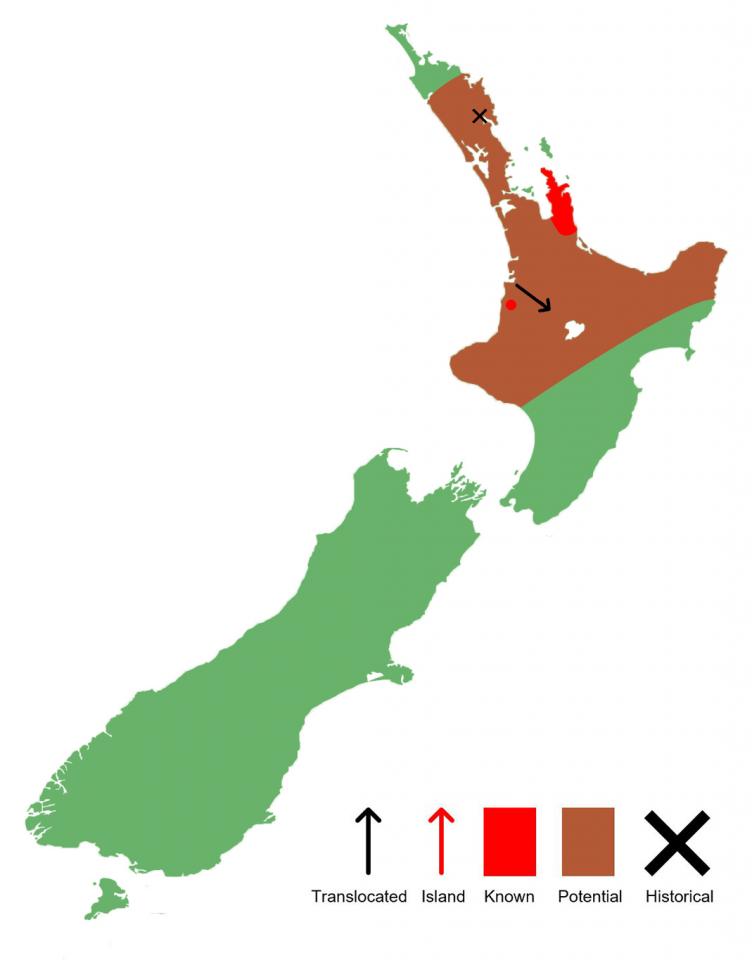

Prior to the colonisation of Aotearoa by humans, Archey’s frogs would have had a much greater distribution, occurring from the East Cape, through to Taranaki, and up into Northland, whilst their sister species, Hamilton's frog (Leiopelma hamiltoni), would have occurred in the southeastern North Island. Today, they are known from the Coromandel Peninsula, and Whareorino Forest (west of Te Kuiti), as well as one translocated population in Pureora Forest. They often occur sympatrically with the semi-aquatic Hochstetter's frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri) (Worthy, 1987; van Winkel et al., 2018; Bishop et al., 2018).

Ecology and habitat

Archey's frogs are nocturnal, and primarily terrestrial, although they are frequently known to climb up vegetation (climbing several metres up into trees and ferns). They inhabit moist native forests between 200-1000 metres above sea level (a.s.l). Frogs emerge from their daytime retreats near dusk and will return to these by dawn. During the day, they typically seek refuge under stones, logs, or in the base of ferns. Their emergence at night is associated with relative humidity, rainfall and the wetness of vegetation. (Bishop et al. 2013; Cree 1989). Archey's frogs seem to be associated with plant communities that typically occur in mature forests, although this pattern of occurrence may have more to do with microclimate and microhabitat preferences (high moisture, litter depth, and complexity of refugia) (Hotham et al., 2023).

Interestingly, Archey's frogs along with their sister species, Hamilton's frog (Leiopelma hamiltoni), exhibit more aggressive defensive tactics than their semi-aquatic cousin the Hochstetter's frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri). Where Hochstetter's frogs tend to quickly move out of harm's way, these terrestrial species take on a rigid headbutting posture. This particular behaviour is strongly associated with the positioning of their secretion glands which are likely a deterrent to would-be predators (Green, 1988).

Social structure

Unlike most frogs, Archey's frog, and other Leiopelma, do not vocalize to communicate with other frogs. Consequently, their breeding behaviour and social behaviour is poorly understood. One study demonstrated that chemical cues from Hamilton's frog (Leiopelma hamiltoni) faeces may play a role in communication and that even size information was able to be communicated. Individuals preferred to spend more time near their own species, rather than faeces from other individuals, and this effect was greatest when the conspecific faeces belonged to a larger frog. Additionally, frogs in this experiment tended to defecate their faeces closer to conspecific faeces, rather than their own (Lee and Waldman 2002).

Although there is little information about territory size, and social interactions in this species, it is likely that as techniques such as radio telemetry become cheaper and more readily available we will learn more about their movements and interactions (see Altobelli et al., 2023).

Archey's frogs also have an interesting paternal care system, whereby the father guards the eggs deposited by the female, which in turn hatch into tailed froglets which climb onto the father's back and are transported around for several weeks until they are fully developed (Bishop et al. 2013).

Breeding biology

As with all of our endemic frog species, the Archey’s frog is oviparous (egg-laying), laying between 4-19 eggs in summer (between December and February). Maturity is reached between four and seven years but is associated with size rather than age (Bell et al., 2023). Mating occurs between September and November, via amplexus (typical frog mating position). After mating has occurred the female deposits her eggs in a suitable nest, which is typically situated beneath logs or stones in damp soil, or within tree cavities (particularly tree-ferns). These eggs are then brooded by the male. The eggs hatch as tailed froglets, which climb onto the father's back and are transported around for several weeks until metamorphosis is complete (a process often referred to as exovivipary) (van Winkel et al. 2018; Bishop et al. 2013; Bell 1978; Cisternas et al., 2023).

Diet

Archey’s frogs are carnivorous, nocturnal predators feeding on a wide range of invertebrate prey. An analysis of the gut contents of wild animals found that their prey consisted of springtails, mites, ants, parasitic wasps, amphipods, and isopods (Shaw et al., 2012), although it is likely that they opportunistically prey on other invertebrates within their forest ecosystems.

Disease

As is the case with all of Aotearoa's herpetofauna, the diseases and parasites of our endemic Leiopelma frogs are poorly understood, and incomplete. However, one of the greatest threats amphibians are facing is the rapid spread of the deadly chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd). This, and other species of Batrachochytrium have impacted many populations of amphibians around the world (Berger et al. 1999). Some evidence indicates that this may have resulted in a major population crash of Archey's frogs in the Coromandel during the 1990's (Bell et al. 2004). However, lab and field studies of Archey's frogs indicate that Leiopelma are highly resistant to this fungus, with some wild individuals persisting after being infected with no obvious adverse effects, whilst captive animals have been seen to eliminate their own infection (Bishop 2009; ).

Whilst, Bd may be of some concern for wild populations, other diseases are more prevalent in captive situations. For example, in captivity, Leiopelma frogs are known to develop metabolic bone disease (MBD) and osteofluorosis (accumulation of fluoride in bones) due to improper husbandry (lack of UVB light, and excess fluoride in water bodies) (Shaw, 2012; Shaw et al., 2012).

Additionally, Archey's frogs are a known host for the trematode Dolichosaccus novaezealandiae, a species seemingly restricted to Aotearoa's native frog species (Allison & Blair, 1987).

Two novel nematodes (Koerneria sp. and Rhabditis sp.) and a novel protozoal infection (Tetrahymena), have been recorded in captive Archey's frogs, but the source be it native or exotic is unknown (Shaw, 2012; Shaw et al., 2012).

Conservation

Archey’s frog are listed as ‘critically endangered’ on the IUCN red list and ‘At risk: Declining’ in the DOC threat classification system (Burns et al. 2017).

Archey's frogs undergo regular monitoring and this will likely be continued to understand population trends through time (Haigh et al. 2007). Translocations are also a valuable tool and translocations have occurred to Pureora Forest, east of Te Kuiti (Cisternas et al. 2021). Predator control is also being undertaken in a number of locations and this will most likely be of importance for the local populations of Archey's frog.

Mammals pose a significant threat to Leiopelma frogs, as molecular diet analysis has demonstrated that both Hochstetter's (Leiopelma hochstetteri) and Archey's frogs are a food source for rats (Egeter et al. 2019; Egeter et al. 2015). Invasive alpine newts (Ichthyosaura alpestris) have also posed a threat to Archey's frogs as they are a vector for disease and have been recorded in close proximity to known Archey's frog populations. Accordingly, it was recommended that alpine newts be eradicated and this control program has appeared to be largely successful (Bell 2016).

Recent studies have indicated that the release of mice during predator-control of rats and mustelids may have an impact on the survival of young frogs, however, this appears to be greatly offset by the survival and associated breeding success of reproductive adults which appear to be at greater predation from the larger mammalian predators (rats, and mustelids) (Germano et al., 2023).

Interesting notes

The specific name 'archeyi' references Sir Gilbert Edward Archey (1890-1974), a former director of the Auckland Institute and Museum, who was responsible for the study and recognition of the life history and habits of our native frogs - namely Hochstetter's frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri) (van Winkel et al., 2018).

The Archey's frog belongs to a clade (group) which includes its sister species Hamilton's frog (Leiopelma hamiltoni), and the extinct Waitomo frog (Leiopelma waitomoensis) (Worthy, 1987).

The skeletal morphology of Archey's and Hamilton's frogs are so similar that it is hard to determine their exact historical distribution based on fossil remains (Worthy, 1987).

References

Allison, B., & Blair, D. (1987). The genus Dolichosaccus (Platyhelminthes: Digenea) from amphibians and reptiles in New Zealand, with a description of Dolichosaccus (Lecithopyge) leiolopismae n. sp. New Zealand journal of zoology, 14(3), 367-374.

Altobelli, J. T., Bishop, P. J., Dickinson, K. J. M., & Godfrey, S. S. (2023). Suitability of radio telemetry for monitoring two New Zealand frogs (Leiopelma archeyi and L. hamiltoni). New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3532.

Bell, B. D. (1978). Observations on the ecology and reproduction of the New Zealand Leiopelmid frogs. Herpetologica, 340-354.

Bell, B. D. (1994). A review of the status of New Zealand Leiopelma species (Anura: Leiopelmatidae), including a summary of demographic studies in Coromandel and on Maud Island. New Zealand journal of zoology, 21(4), 341-349.

Bell, B. D. (2010). The threatened Leiopelmatid frogs of New Zealand: Natural history integrates with conservation. Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 5(3), 515-528.

Bell, B. D. (2011). Long term population monitoring of the Maud Island frog and Archey’s frog, Victoria University of Wellington. FrogLog, 99, 40-41.

Bell, B. D. (2016). A review of potential alpine newt (Ichthyosaura alpestris) impacts on native frogs in New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 46(3-4), 214-231.

Bell, B. D., Carver, S., Mitchell, N. J., & Pledger, S. (2004). The recent decline of a New Zealand endemic: how and why did populations of Archey's frog Leiopelma archeyi crash over 1996–2001?. Biological Conservation, 120(2), 189-199.

Bell, B. D., Daugherty, C. H., & Hitchmough, R. A. (1998). The taxonomic identity of a population of terrestrial Leiopelma (Anura: Leiopelmatidae) recently discovered in the northern King Country, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 25(2), 139-146.

Bell, B. D., Shirley, A., & Pledger, S. (2023). Post-metamorphic body growth and remarkable longevity in Archey's frog and Hamilton's frog in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3528.

Bell, B. D., & Wassersug, R. J. (2003). Anatomical features of Leiopelma embryos and larvae: implications for anuran evolution. Journal of Morphology, 256(2), 160-170.

Benno Meyer-Rochow, V., & Pehlemann, F. W. (1990). Retinal organisation in the native New Zealand frogs Leiopelma archeyi, L. hamiltoni, and L. hochstetteri (Amphibia: Anura; Leiopelmatidae). Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 20(4), 349-366.

Berger, L., Speare, R., & Hyatt, A. (1999). Chytrid fungi and amphibian declines: overview, implications and future directions. Declines and disappearances of australian frogs. Environment Australia, Canberra, 1999, 23-33.

Bishop, P. J., Speare, R., Poulter, R., Butler, M., Speare, B. J., Hyatt, A., Olsen, V., & Haigh, A. (2009). Elimination of the amphibian chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis by Archey’s frog Leiopelma archeyi. Diseases of aquatic organisms, 84(1), 9-15.

Bishop, P. J., Daglish, L. A., Haigh, A., Marshall, L. J., Tocher, M., & McKenzie, K. L. (2013). Native frog (Leiopelma spp.) recovery plan, 2013-2018: Threatened species recovery plan 63. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand.

Bradfield, K. S. (2004). Photographic identification of individual Archey’s frogs, Leiopelma archeyi, from natural markings: DOC Science Internal Series 191. Department of Conservation, Wellington. 36 p.

Burns, R. J., Bell, B. D., Haigh, A., Bishop, P., Easton, L., Wren, S., Germano, J., Hitchmough, R. A., Rolfe, J. R., & Makan, T. (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand amphibians, 2017. New Zealand Threat Classification Series 25: Department of Conservation, Wellington. 7 p.

Carr, L. M., McLenachan, P. A., Waddell, P. J., Gemmell, N. J., & Penny, D. (2015). Analyses of the mitochondrial genome of Leiopelma hochstetteri argues against the full drowning of New Zealand. Journal of Biogeography, 42(6), 1066-1076.

Cisternas Tirapegui, J. (2019). Translocation management of Leiopelma archeyi (Amphibia, Anura: Leiopelmatidae) in the King country (Doctoral dissertation, University of Otago).

Cisternas, J., Easton, L. J., & Bishop, P. J. (2023). Use of dead tree-fern trunks as oviposition sites by the terrestrial breeding frog Leiopelma archeyi. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3533.

Cisternas, J., Easton, L. J., Germano, J. M., & Bishop, P. J. (2022). Demographic estimates to assess the translocation of a threatened New Zealand amphibian. Wildlife Research, 50(1), 47-56.

Cisternas, J., Easton, L., Germano, J. M., Haigh, A., Gibson, R., Haupokia, N.,& Bishop, P. J. (2021). Review of two translocations used as a conservation tool for an endemic terrestrial frog, Leiopelma archeyi, in New Zealand. Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021. Case studies from around the globe, 56-64.

Cree, A. (1989). Relationship between environmental conditions and nocturnal activity of the terrestrial frog, Leiopelma archeyi. Journal of Herpetology, 61-68.

Daugherty, C. H., Bell, B. D., Adams, M., & Maxson, L. R. (1981). An electrophoretic study of genetic variation in the New Zealand frog genus Leiopelma. New Zealand journal of zoology, 8(4), 543-550.

Daugherty, C. H., Maxson, L. R., & Bell, B. D. (1982). Phylogenetic relationships within the New Zealand frog genus Leiopelma—immunological evidence. New Zealand journal of zoology, 9(2), 239-242.

Easton, L. (2018). Taxonomy and genetic management of New Zealand's Leiopelma frogs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Otago).

Easton, L. J., Rawlence, N. J., Worthy, T. H., Tennyson, A. J., Scofield, R. P., Easton, C. J., Bell, B. D., Whigham, P. A., Dickinson, K. J. M., & Bishop, P. J. (2018). Testing species limits of New Zealand’s leiopelmatid frogs through morphometric analyses. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 183(2), 431-444.

Eda, A. R. A. R., Bishop, P. J., Altobelli, J. T., Godfrey, S. S., & Stanton, J. L. (2023). Screening for Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in New Zealand native frogs: 20 years on. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3531.

Egeter, B., Bishop, P. J., & Robertson, B. C. (2011). DNA detects frog predation, University of Otago. FrogLog, 99, 36-37.

Egeter, B., Robertson, B. C., & Bishop, P. J. (2015). A synthesis of direct evidence of predation on amphibians in New Zealand, in the context of global invasion biology. Herpetological Review, 46(4), 512-519.

Egeter, B., Roe, C., Peixoto, S., Puppo, P., Easton, L. J., Pinto, J., Bishop, P. J., & Robertson, B. C. (2019). Using molecular diet analysis to inform invasive species management: A case study of introduced rats consuming endemic New Zealand frogs. Ecology and Evolution, 9(9), 5032-5048.

Eggers, K. E. (1998). Morphology, ecology and development of leiopelmatid frogs (Leiopelma spp.), in Whareorino Forest, New Zealand: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Ecology at Massey University (Doctoral dissertation, Massey University).

Germano, J. M., Bridgman, L., Thygesen, H., & Haigh, A. (2023). Age dependent effects of rat control on Archey's frog (Leiopelma archeyi) at Whareorino. New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3529.

Germano, J. M., Earl, R., Tocher, M., Pearce, P., & Christie, J. (2023). The conservation long game: Leiopelma species climate envelopes in New Zealand under a changing climate. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3535.

Gibson, R., & Fraser, I. (2011). Auckland Zoo - Captive Breeding. FrogLog, 99, 32-33.

Green, D. M. (1988). Antipredator behaviour and skin glands in the New Zealand native frogs, genus Leiopelma. New Zealand journal of zoology, 15(1), 39-45.

Green, D. M. (2002). Chromosome polymorphism in Archey's frog (Leiopelma archeyi) from New Zealand. Copeia, 2002(1), 204-207.

Green, D. M., & Cannatella, D. C. (1993). Phylogenetic significance of the amphicoelous frogs, Ascaphidae and Leiopelmatidae. Ethology Ecology & Evolution, 5(2), 233-245.

Green, D. M., & Sharbel, T. F. (1988). Comparative cytogenetics of the primitive frog, Leiopelma archeyi (Anura, Leiopelmatidae). Cytogenetic and Genome Research, 47(4), 212-216.

Green, D. M., Sharbel, T. F., Hitchmough, R. A., & Daugherty, C. H. (1989). Genetic variation in the genus Leiopelma and relationships to other primitive frogs. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 27(1), 65-79.

Haigh, A., Pledger, S., & Holzapfel, A. S. (2007). Population monitoring programme for Archey's frog (Leiopelma archeyi): pilot studies, monitoring design and data analysis. Science & Technical Pub., Department of Conservation.

Hotham, E. R., Muchna, K., & Armstrong, D. P. (2023). Abundance of Leiopelma archeyi on the Coromandel Peninsula in relation to habitat characteristics and land-use. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3527.

Irisarri, I., San Mauro, D., Green, D. M., & Zardoya, R. (2010). The complete mitochondrial genome of the relict frog Leiopelma archeyi: insights into the root of the frog Tree of Life. Mitochondrial DNA, 21(5), 173-182.

Melzer, S., & Bishop, P. J. (2010). Skin peptide defences of New Zealand frogs against chytridiomycosis. Animal Conservation, 13, 44-52.

Melzer, S., & Bishop, P. J. (2011). Just Juice? Attempting to unravel the secrets of skin secretions in New Zealand's endemic frogs. FrogLog, 99, 37-38.

Melzer, S., Clerens, S., & Bishop, P. J. (2011). Differential polymorphism in cutaneous glands of archaic Leiopelma species. Journal of Morphology, 272(9), 1116-1130.

Newman, D. G. (1996). Native frog (Leiopelma spp.) Recovery plan: Threatened species recovery plan No. 18. Wellington: Department of Conservation.

Newman, D. G., Bell, B. D., Bishop, P. J., Burns, R., Haigh, A., Hitchmough, R. A., & Tocher, M. (2010). Conservation status of New Zealand frogs, 2009. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 37(2), 121-130.

Perfect, A. J., & Bell, B.D. (2005). Assessment of the impact of 1080 on the native frogs Leiopelma archeyi and L. hochstetteri: DOC Research & Development Series 209. Department of Conservation, Wellington. 58 p.

Powell, J., Matthaei, C. D., & Godfrey, S. S. (2023). Colour variation and behaviour of the cryptic New Zealand frog Leiopelma archeyi. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3534.

Ramírez Saavedra, P. A. (2017). Behavioural patterns of two native Leiopelma frogs and implications for their conservation: a thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology and Biodiversity (Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University).

Reilly, S., Essner Jr, R., Wren, S., Easton, L., & Bishop, P. J. (2015). Movement patterns in leiopelmatid frogs: insights into the locomotor repertoire of basal anurans. Behavioural Processes, 121, 43-53.

Shaw, S. D. (2011). Auckland Zoo - Frog Diseases. FrogLog, 99, 33.

Shaw, S. D. (2012). Diseases of New Zealand native frogs (Doctoral dissertation, James Cook University).

Shaw, S. D., Berger, L., Bell, S., Dodd, S., James, T. Y., Skerratt, L. F., Bishop, P. J., & Speare, R. (2014). Baseline cutaneous bacteria of free-living New Zealand native frogs (Leiopelma archeyi and Leiopelma hochstetteri) and implications for their role in defense against the amphibian chytrid (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis). Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 50(4), 723-732.

Shaw, S. D., Berger, L., Harvey, C., Alley, M. R., Bishop, P. J., & Speare, R. (2017). Adenomatous hyperplasia of the mucous glands in captive Archey’s frogs (Leiopelma archeyi). New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 65(3), 140-146.

Shaw, S. D., Bishop, P. J., Berger, L., Skerratt, L. F., Garland, S., Gleeson, D. M., Haigh, A., Herbert, S., & Speare, R. (2010). Experimental infection of self-cured Leiopelma archeyi with the amphibian chytrid Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Diseases of aquatic organisms, 92(2-3), 159-163.

Shaw, S. D., Bishop, P. J., Harvey, C., Berger, L., Skerratt, L. F., Callon, K., Watson, M., Potter, J., Jakob-Hoff, R., Goold, M., Kunzmann, N., West, P., & Speare, R. (2012). Fluorosis as a probable factor in metabolic bone disease in captive New Zealand native frogs (Leiopelma species). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 43(3), 549-565.

Shaw, S. D., Bishop, P. J., Skerratt, L. F., Myhre, J., & Speare, R. (2014). Historical trends in frog populations in New Zealand based on public perceptions. New Zealand journal of zoology, 41(1), 10-20.

Shaw, S. D., Skerratt, L. F., Kleinpaste, R., Daglish, L., & Bishop, P. J. (2012). Designing a diet for captive native frogs from the analysis of stomach contents from free-ranging Leiopelma. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 39(1), 47-56.

Shaw, S. D., Speare, R., Lynn, D. H., Yeates, G., Zhao, Z., Berger, L., & Jakob-Hoff, R. (2011). Nematode and ciliate nasal infection in captive Archey's frogs (Leiopelma archeyi). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 42(3), 473-479.

Stephenson, E. M. (1951). The anatomy of the head of the New Zealand frog, Leiopelma. The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 27(2), 255-305.

Stephenson, N. G. (1951). On the Development of the Chondrocranium and Visceral Arches of Leiopelma archeyi. The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 27(2), 203-253.

Thorsen, M. (1999). Resurvey of Archey's frogs, Mt Moehau, 24 December 1998. Department of Conservation.

Thurley, T., & Bell, B. D. (1994). Habitat distribution and predation on a western population of terrestrial Leiopelma (Anura: Leiopelmatidae) in the northern King Country, New Zealand. New Zealand journal of zoology, 21(4), 431-436.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M., Hitchmough, R. 2018. Reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand – a field guide. Auckland university press, Auckland New Zealand.

Waldman, B. (2011). Brief Encounters with Archey’s Frog. FrogLog, 99, 41-43.

Worthy, T. H. (1987). Osteology of Leiopelma (Amphibia: Leiopelmatidae) and descriptions of three new subfossil Leiopelma species. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 17(3), 201-251.

Worthy, T. H. (1987). Palaeoecological information concerning members of the frog genus Leiopelma: Leiopelmatidae in New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 17(4), 409-420.

Wren, S., Bishop, P. J., Beauchamp, A. J., Bell, B. D., Bell, E., Cisternas, J., Dewhurst, P., Easton, L., Gibson, R., Haigh, A., Tocher, M., & Germano, J. M. (2023). A review of New Zealand native frog translocations: lessons learned and future priorities. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), 3538.