- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Otagense

Oligosoma otagense

Otago skink

Oligosoma otagense

(McCann, 1955)

Length: SVL up to 142mm, with the tail being much longer than the body length

Weight: up to 43.5 grams

Description

Otago skinks are the largest species of skink in the South Island of New Zealand, with a snout-vent-length (SVL) up to 142 mm. These beautifully-marked lizards are comprised of two major populations, that are geographically separated, and exhibit a relatively high level of genetic divergence (Chapple et al. 2012). While there is overlap in patterns, coloration, and morphology, the two groups can loosely be described as follows:

1. Eastern population:

Dorsal surface typically vivid black with pale grey, greenish, yellow, gold, or golden-brown blotches. These blotches are often indistinct and irregular. The basal coloration tends to become very faded with age and often bears many pale brown or yellow flecks. Blotches often particularly prominent on the dorsolateral region and will continue down onto intact tail. These often join together on the tail giving a uniform appearance. A thick pale streak or blotch typically runs from above the nostril through to above the eye. The upper and lower supralabials and infralabials (lip scales) are typically this colour too. Lateral surfaces similar to dorsal surface with lower lateral surface becoming cream, grey, or off-white. This portion of the lateral surface is often mottle with black and has small, irregular blotches or flecks. Ventral surface grey, off-white, cream, or yellowish. Eye colour black. Intact tail longer than body (SVL). Soles of feet grey to black (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008).

2. Western population:

Dorsal surface typically vivid black with pale olive-greenish, yellow, grey, gold, or golden-brown blotches. These blotches are typically more bold and distinct, giving the appearance of a vivid black basal colour with prominent, well-defined blotches. Blotches often slightly larger on the dorsolateral region, as they will extend down onto the lateral surface. These blotches will also continue down onto intact tail. These often join together on the tail giving a uniform appearance. A thick pale streak or blotch typically runs from above the nostril through to above the eye. The upper and lower supralabials and infralabials (lip scales) are typically this colour too. Lateral surfaces similar to dorsal surface, sometimes with dorsolateral blotches forming defined lateral bands that extend down to the ventral surface. The lateral surfaces are typically more defined and less irregular/mottled-looking than the eastern population. Lower lateral surface cream, grey, or off-white. Ventral surface grey, off-white, cream, or yellowish. Eye colour black. Intact tail longer than body (SVL). Soles of feet grey to black (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008).

Life expectancy

Wild Otago skinks are known to live up to at least 21 years, but have lived up to 44 years in captivity (van Winkel et al. 2018).

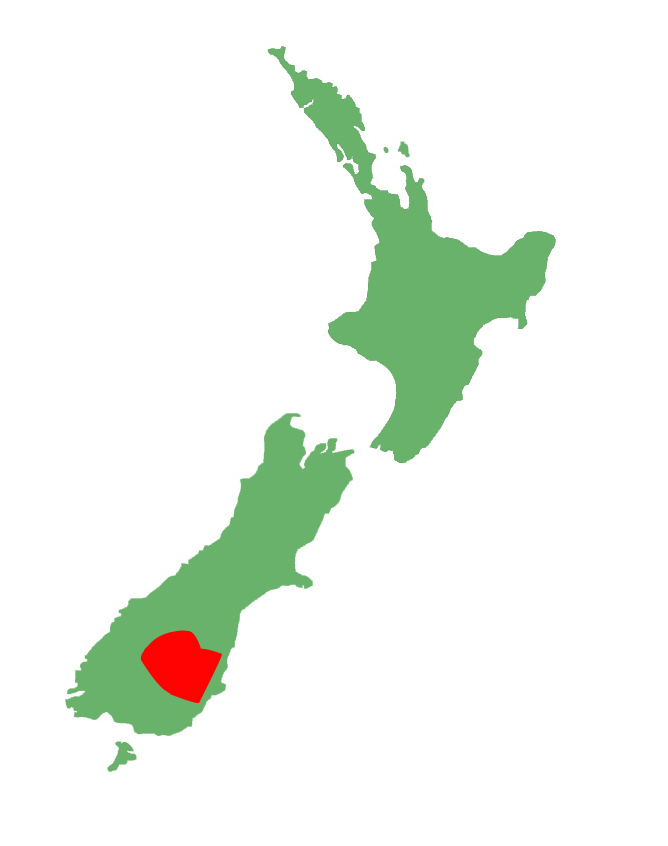

Distribution

Restricted to the Otago Region and Lakes District. Known from around Lindis Pass and Lake Hawea areas (western population), and around Macraes Flat and Middlemarch (eastern population). Otago skinks were once widespread throughout these areas but are now thought to occupy only 8% of their former or potential range (Houghton and Linkhorn 2002).

Ecology and habitat

Otago skinks are diurnal, terrestrial, and saxicolous. They are a strongly heliothermic species that sun basks avidly. Their emergence behaviour is highly dependent on good weather conditions, with a peak of activity in Autumn, and they will remain concealed within cracks, crevices and holes during overcast, cold, or windy conditions (Marshall 2001; Coddington and Cree 1997). Otago skinks are associated with schist rock outcrops that are surrounded by tussockland and other native vegetation. They are are also typically found along deep rocky gullys with streams (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008; Whitaker and Loh 1995; Towns et al. 1984). This species is also known to move long distances through habitat, with measured home ranges (100% Minimum Convex Polygon method) varying from 200 - 5,400 m2 (Germano 2007).

Social structure

Unlike most New Zealand lizards, Otago skinks have actually been studied scientifically in the context of social behaviour. In one study, skinks were typically observed being either solitary, or belonging to small groups of 2-8 individuals. In this study, social interaction between adults and subadults appeared to be stable throughout the seasons (whereas there was no stability in juvenile interaction patterns) and it has been suggested that in the population studied, adults largely drive the stability of social interactions. This species is often observed in large basking ground, particularly with juveniles and it is thought that this could be a group protection strategy to mitigate attacks from predators, or larger conspecifics. It is also possible that there is some extent of parental care in Otago skinks, as juveniles have been observed interacting with adult females, and the presence of an adult skink may afford juveniles protection. (Elangovan et al. 2021).

Breeding biology

Otago skinks reach reproductive maturity at 4-6 years and typically breed annually or biennially. Mating usually occurs in March, which is then followed by sperm storage in females. Gestation takes between 4-5 months with between two and four offspring born in late summer between January and March (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008; Cree 1994). In captivity, litters of up to six have been recorded (Keall pers. comm. 2016).

Diet

Otago skinks consume large quantities of small-bodied beetles and large-bodied flies and native fruits such as those from Coprosma taylorae and Leucopogon fraseri. While there does not appear to be any major dietary differences between Otago skinks of different age or sex, some dietary specialization between Otago skinks and grand skinks (Oligosoma grande) have been observed in late summer. Accordingly, habitat that lacks these plants is unlikely to be suitable (Tocher 2003).

Disease

Otago skinks are known hosts for several ectoparasitic mites including Odontacarus lygosomae, Ophionyssus scincorum, and Neotrombicula naultini (although the latter may have been collected from a captive specimen). They are also known hosts for the blood parasite Hepatozoon lygosomarum.

Conservation strategy

Otago skinks are classified by The Department of Conservation as ‘nationally endangered’ (Hitchmough et al. 2016). DOC have a recovery plan in place for Otago and grand skinks (Oligosoma grande) (Collen et al. 2009; Whitaker and Loh 1995) and dedicated conservation efforts have involved intensive predator control, predator-proof fences and captive breeding programs. The eradication or reduction of introduced mammalian predators appears to be highly important for the persistence of this species given their large size. Accordingly, translocations to predator-free sanctuaries and intensive trapping have been highly useful for preserving populations of this species, whereas unmanaged populations have declined severely (Norbury et al. 2014; Reardon et al. 2012; Whitmore et al. 2011).

Interesting notes

The eastern and western Otago skink populations are estimated to have diverged during the mid-Pliocene, about three million years ago. There are no genetic haplotypes shared between these two regions and the divergence is thought to account for 95% of the genetic diversity within Otago skinks as a species. Additionally, within both these regions, there is strong genetic structuring. Consequently it has been suggested that these groups be treated as different management units (Chapple 2012), and given that other recognized species in New Zealand have even shallower levels of genetic and morphological divergence, it is possible that one day these populations will be described as different species.

References

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2008). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers Ltd.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M., Hitchmough, R. 2018. Reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand – a field guide. Auckland university press, Auckland New Zealand.