- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Hoplodactylus Tohu

Hoplodactylus tohu

Mokomoko a Tohu | Tohu gecko

Hoplodactylus tohu

(Scarsbrook et al., 2023)

Length: SVL up to 120mm

Weight: Unknown

Description

New Zealand's second largest gecko, and the largest species of gecko in the South Island.

Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos are large and robust in build. The dorsal colouration may be various shades of grey or olive brown, with a distinctive pale crescent-shaped marking on the nape of the neck, and pale irregular crossbar-shaped splotches down the dorsum which continue to the base of the tail. The underside is pale and usually a uniform grey but can be softly speckled/blotched. Duvaucel’s geckos have a pink mouth and tongue. The forehead is slightly concave with yellow eyes, prominent brillar-folds (scales over the eyes), and large oval openings for the ears.

There are significant genetic and morphological differences between this species (occurring in Cook Strait) and the northern species of Hoplodactylus (occurring from the Bay of Plenty northwards). Duvaucel's geckos (Hoplodactylus duvaucelii) are generally much larger, longer (110-161mm SVL) and more robust, with a proportionally longer snout and less-defined markings. Whilst, Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos are generally smaller (95-120mm SVL), have a proportionally shorter / blunter snout, a more pronounced brillar fold, and have more well-defined blotched markings. Infralabial scales become gradually smaller in Duvaucel's geckos versus often abruptly smaller after the 4th infralabial in Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos.

Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos will occasionally vocalise which has been described as squeaks, squeals, croaking and coughing.

Life expectancy

Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos have been reported to live over 50 years in the wild.

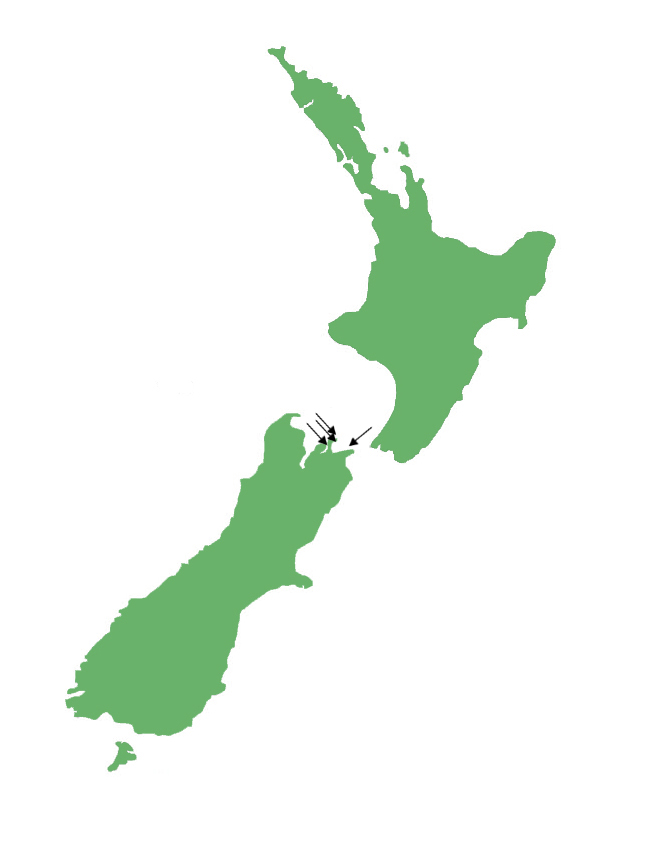

Distribution

Known only from the Marlborough Sounds / Cook Strait area. Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos survived only on the Brothers Islands, Trio Islands, and Sentinel Rock. They have since been translocated to two further islands in the Marlborough Sounds and to Mana Island off the south Wellington Coast (outside of their historic range).

Fossil records show that Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos once had a much wider distribution including large parts of the mainland South Island as far south as Otago.

Ecology and habitat

A largely nocturnal species, Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos can remain active at low temperatures but actively regulate their body temperature by sun basking. During the day they tend to hide in tree hollows, under logs, stones or bark, rock crevices or in petrel burrows.

Social structure

Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos are tolerant of members of the same species and may form social aggregations. These groups will usually contain only one male.

Breeding biology

Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos give birth to live young and have a low annual reproductive output (maximum of two offspring annually / biennially). Gestation has been variously reported as between five months to longer than a year. Individuals become sexually mature at around seven years old.

Diet

The diet of Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos is largely insectivorous. However, they will also eat plant material, nectar, and fruit. There are records of the closely-related Duvaucel’s geckos predating other lizards and the eggs of shearwaters. Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos have also been reported consuming the berries of Taupata (Coprosma repens) in the wild (Nick Harker pers. obs. 14 January 2020).

Disease

Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos are known to harbour a number of ecto- and endoparasites (internal and external).

Populations of Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos on the Trio Islands have been recorded as a host for the ectoparasitic mite Ophionyssus galeotes.

In the wild, Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos have also been observed with unusual warty growths, the cause of which is currently unknown (Nick Harker, pers. obs. January 2020).

Conservation strategy

Moko a Tohu/Tohu geckos are currently classified as 'Threatened - Nationally Increasing' They have been translocated to two additional islands in the Marlborough Sounds, and also to Mana Island off the south Kapiti / Wellington Coast (the latter being outside of their historic range).

Interesting notes

The specific name 'tohu' was given to the species by Te Ātiawa o Te Waka-a-Māui, and is a tribute to Tohu Kākahi. Tohu Kākahi was a pacifist who was taken prisoner by British forces during the invasion of Parihaka in Taranaki. His imprisonment saw him moved right across the historical range of the gecko that bears his name - from Whakatū (Nelson), past Ngāwhatu-Kai-ponu (the Brothers Islands), and into Ōtepoti (Dunedin).

In the mid-1900s the Moko a Tohu/Tohu gecko was described as a separate species Rhacodactylus trachyrhynchus (GUIBÉ, 1954), however, they were still regarded by some to be a regional variant of the Duvaucel's gecko (Hoplodactylus duvaucelii) until their description in 2023.

Despite being long-recognised as 'different', some researchers felt that the genetic and morphological variation between the Duvaucel's gecko (Hoplodactylus duvaucelii), and Moko a Tohu/Tohu gecko could be accounted for with a north-south cline. However, more recent palaeoecological work, looking at ancient DNA and morphology of Duvaucel's gecko subfossils has provided conclusive evidence that the two groups represent distinct, geographically separated taxa.

Moko a Tohu and their sister species Duvaucel's gecko belong to the "broad-toed" clade of Aotearoa's gecko fauna. In this group they sit basally being the sister genera to the Woodworthia genus.

References

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishing.

Robb, J. (1986). New Zealand Amphibians & Reptiles (Revised). Auckland: Collins, 128 pp.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A Field Guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

Moko a Tohu/Tohu gecko (Sentinel Rock, Marlborough Sounds). © Nick Harker