- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Pluvialis

Oligosoma pluvialis

Te Wāhipounamu Skink

Oligosoma pluvialis

(Jewell, 2022)

Length: SVL up to 80 mm, with the tail being equal to or longer than the body length

Weight: up to 6 grams

Description

The Te Wāhipounamu skink is a beautiful, and highly-variable relative of the cryptic skink, differentiated from the latter by a distinctively keeled tail (although seemingly absent in some eastern clade populations). It is tentatively comprised of four previously distinct taxa, which form western (Big Bay skink, and mahogany skink), and eastern (Humboldt skink, and pallid skink) clades. As such each "population" has its own unique appearance:

Big Bay skink: Dorsal surfaces range from chestnut to dark brown with a thick and distinctive black or dark brown mid-dorsal stripe. The lateral surfaces (sides) typically bear a thick dark lateral band bordered by a pale cream lateral stripe and mid-lateral stripe. The ventral (lower) surfaces are characterised by a copper-brown or yellow-brown belly and grey throat with black speckles. Possesses a keeled tail (i.e. raised scales). Eye colour brownish. 18-20 subdigital lamellae. Soles of feet yellow-brown.

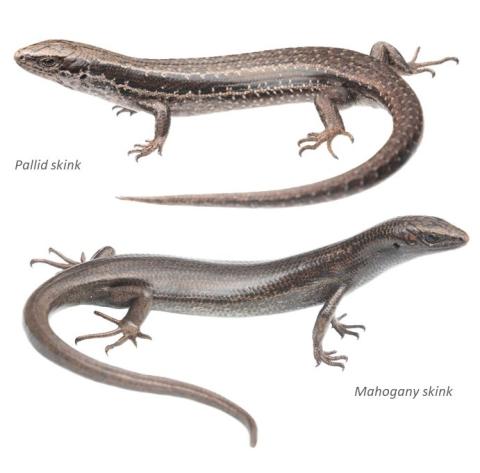

Mahogany skink: Dorsal surfaces are often uniform, ranging from warm chestnut to dark brown, but may on occasion exhibit dark flecks or rudimentary stripes. Exhibits a dull black mid-dorsal stripe, although this may be indistinct. Dorsolateral stripes are present where the sides and the upper surfaces meet, however, they are thin, dull light brown and highly indistinct. The lateral surfaces (sides) bear a dull mid-lateral stripe. The ventral (lower) surfaces are characterised by a deep yellow belly, and a grey throat with moderate to bold black flecking. Possesses a keeled tail (i.e. raised scales) Eye colour pale green-grey. Subdigital lamellae 20-23. Soles of feet black.

Humboldt skink: One of the larger forms of the Te Wāhipounamu skink, reaching an SVL of up to 80 mm. Their dorsal surfaces range from mid to dark brown with a faintly marked back (a few flecks and an indistinct mid-dorsal stripe). The lateral surfaces (sides) exhibit a dark band bordered by indistinct pale notched dorsolateral and mid-lateral stripes. The ventral (lower) surfaces are characterised by a yellow belly with a uniform grey throat.

Pallid skink: Dorsal surfaces are typically light chestnut brown, dark brown, or grey-brown with scattered spots, blotches and broken stripes. Dark flecking is particularly prominent on the top of the head. The lateral surfaces (sides) bear dull, clearly notched dorsolateral and mid-lateral stripes. The ventral surfaces are creamy-grey in colouration and are occasionally lightly mottled or strongly blotched with pale and dark flecks.

Life expectancy

Unknown.

Distribution

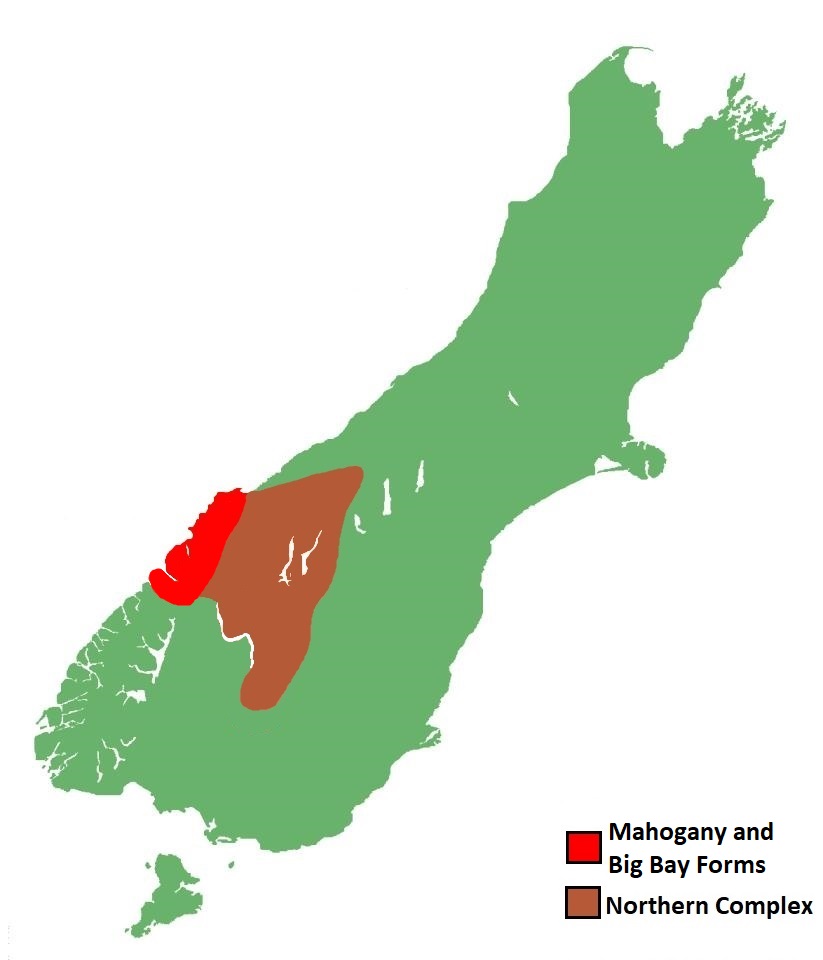

Big Bay skink: Known from northern Fiordland and South Westland from Big Bay to Barn Bay and the Cascade Plateau. May be a lowland specialist, as no confirmed sightings have occurred in alpine/subalpine habitat.

Mahogany skink: Known only from the Llawrenny Peaks in Fiordland (Transit Gully, Sinbad Gully, Mitre Peak).

Humboldt skink: Lake Wakatipu to adjacent Fiordland peaks such as Mt Earnslaw, Humboldt Mountains, and Earl Mountains.

Pallid skink: Known from Southland and western Otago including Mt Cardrona, Tapuae-o-Uenuku/Hector Mountains, Coronet Peak, Mid Dome, and Mataura Range. It is possible that this species exists elsewhere.

Ecology and habitat

Te Wāhipounamu skinks may differ in habitat use and ecology depending on geographic form, however, their habitat use and behaviour are ultimately somewhat similar. These skinks are diurnal and terrestrial (occasionally semi-arboreal climbing into tall shrubs). While they do sun bask, they typically do so in a cryptic manner, while hiding in dense vegetation or near the entrance to their stone retreats. Consequently, they can sometimes be difficult to observe basking. These skinks have been recorded in a variety of habitats from the lowland right up to at least 1825 m (a.s.l). They exist in habitats such as tussocklands, grasslands, scrublands, herbfields, wetlands, and rocky areas (e.g. rocky beaches, shrubland, screes, tallus, vertical rock walls)(van Winkel et al. 2018).

Social structure

Unknown.

Breeding biology

Poorly understood. Females produce 1-3 young annually (at least in lowland areas) in summer (January-March).

Diet

Feeds on small invertebrates and on the fruits of native shrubs, and the nectar of flowers.

Disease

Known host for at least one species of ectoparasitic mite.

Conservation strategy

This species is not being actively managed. The previously recognised taxa that comprise this species concept range from "At Risk - Declining" (mahogany, pallid, and Humboldt skinks) to "Threatened - Nationally Vulnerable" (Big Bay skink), effectively resulting in the entire population being assigned the lower classification, due to the overall distribution and population estimates being combined.

Interesting notes

The Latin name 'pluvialis' is a reference to the high rainfall (pluvia - "rain") that is observed over a significant part of the species' range.

Some populations of Te Wāhipounamu skink (e.g., pallid skinks) at very high elevations appear to be somewhat naive to predators and have exhibited limited escape responses to researchers (pers.comm. Dr. Mandy Tocher).

Prior to their description in 2022, several populations of the Te Wāhipounamu skink were recognized as potentially distinct taxa (Hitchmough et al. 2021). There are still some questions to the validity of some of these populations being placed within the species concept and as such further genetic and morphological research will need to be carried out in order to determine how they relate to other members of the 'cryptic skink complex'.

References

Jewell, T. (2008). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland.

Jewell, T. (2019). Skinks of southern New Zealand. A field guide. Edition 4.

Jewell, T. (2022). Oligosoma pluvialis n. sp. (Reptilia: Scincidae) from Te Wāhipounamu/South West New Zealand. Jewell Publications, Occasional Publication #2022H.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M., Hitchmough, R. 2018. Reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand – a field guide. Auckland university press, Auckland New Zealand.