- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Pachysomaticum

Oligosoma pachysomaticum

Coromandel skink

Oligosoma pachysomaticum

(Robb, 1975)

Length: SVL up to 84mm, total body length (including tail) up to 165mm.

Weight: unknown

Description

A moderately robust species with a short, deep snout and a relatively large eye. Dorsum light brown with numerous small dark flecks and occasionally also small pale flecks. Sides grey to grey-brown with irregular small, pale blotches that are enclosed by dark edges, and with an indented blackish band passing from the ear up along the shoulders to behind the level of the forelimbs. The belly is pale with numerous dark flecks. The head sports a ‘tear-drop’ marking under each eye (white with black edging); the remainder of the ‘lips’ often with much finer pale denticulate (‘tooth-like’) markings. Tail is short and thick, tapering abruptly.

Co-exists with Whitaker's skink (Oligosoma whitakeri) with which it is easily confused. However, Coromandel skinks have a whitish undersurface with many dark flecks, whereas, Whitaker’s skinks have a yellow-orange underside with no, or few dark flecks. Also co-exists with several other species that are either much larger (e.g. robust skink) or much smaller (e.g. copper skink, shore skink). Previously included in the definition of the marbled skink (Oligosoma oliveri) but substantially smaller in size with a comparatively larger eye, more flecked (versus marbled) colour pattern and larger body scales.

Life expectancy

Unknown.

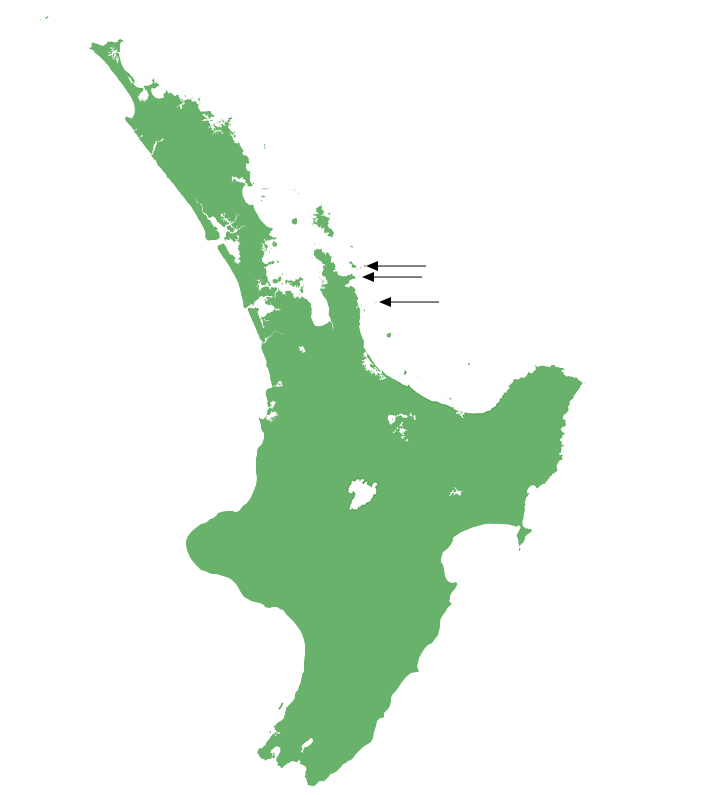

Distribution

Restricted to the Alderman Islands, Ohinau Island, and Mercury Islands off the eastern coast of the Coromandel Peninsula.

Ecology and habitat

Coromandel skinks are nocturnal with a peak of activity after dusk (probably employing a ‘sit-and-wait’ hunting strategy for the remainder of the night) and occasionally also appear by day, but rarely sun-bask. They primarily inhabit deep leaf litter on the floor of coastal forest and scrub, sharing this environment with the larger robust and Whitakers skinks and the much smaller copper skink.

Social structure

Unknown, but presumed to be solitary.

Breeding biology

Viviparous. Gravid females produce 2-4 young per litter in early autumn (March/April).

Diet

Coromandel skinks are omnivorous, feeding on small invertebrates as well as fruit from native plants, and have been recorded consuming the berries of nightshade (Solanum nodiflorum).

Disease

Unknown.

Conservation strategy

Coromandel skinks would almost certainly have existed on the mainland until the arival of rats 800 years ago, and subfossil bone deposits in the Bay of Plenty area appear to be from this species. However, they appear to have a low tolerance to mammalian predators and eventually became restricted to just a few small island sanctuaries off the Coromandel Peninsula. The population is stable now and thought to be growing due to the gradual recovery of forest cover on the islands. The translocation of specimens to other islands within the Mercury Islands, such as Korapuki Island, have also resulted in the successful establishment of new populations.

Interesting notes

The Coromandel skink was originally described by Joan Robb (1975) as a unique species, but was soon synonymised with the marbled skink (Oligosoma oliveri) by Graham Hardy (1977). After many years of taxonomic confusion, which also involved the Hauraki skink (Oligosoma townsi), it was eventually reinstated as a valid species of its own by Tony Jewell (2019).

A close genetic similarity between the Coromandel and marbled skinks belies a fascinating contrast in terms of their distribution, ecology and conservation status, for they are polar opposites in many respects. While the Coromandel skink has suffered a massive distribution contraction at the hands of exotic predators and habitat loss, its existence is probably more secure than Marbled skinks. Marbled skinks are the top skink on their island and probably still occur throughout their natural range, but their large size and natural confinement to a small number of very close islands (i.e. none separated by more than 300 metres, within easy rat swimming distance) now leaves their entire population vulnerable to a rapid extinction, should rats ever manage to colonize the Poor Knights.

The Coromandel skink, along with its sister taxa (the marbled skink and Whitaker's skink) sit within clade 4 (the teardrop skink complex) of the Oligosoma genus, with the Hauraki skink being their closest relative within the group.

References

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishing.

Robb, J. (1986). New Zealand Amphibians & Reptiles (Revised). Auckland: Collins, 128 pp.

Towns, D. R., & Hayward, B. W. (1973). Reptiles of the Aldermen Islands. Tane, 19, 93-102.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp