- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma chionochloescens

Oligosoma chionochloescens

Tussock skink

Oligosoma chionochloescens

(Jewell, 2022)

Length: SVL up to 82mm, with the tail being equal to or slightly longer than the body length

Weight: unknown

Description

The tussock skink is a sleek and highly variable member of the grass skink complex. They were initially considered to be a southern clade of the southern grass skink (Oligosoma aff. polychroma Clade 5) but were separated from the latter in 2022 based on an abrupt contact zone in which head shape and colour pattern varied markedly (Jewell, 2022). As such, the aptly named tussock skink represents the southernmost member of the grass skink lineage.

The tussock skink is generally considered to have two colour morphs which differ markedly in pattern and colouration, these are:

Striped morph: This is the most commonly encountered form, being fairly similar to other members of the grass skink complex. They are characterised by their cream-brown to tan-brown dorsal (upper) surfaces, distinctive dark mid-dorsal stripe extending down the tail, and conspicuous cream dorsolateral stripes that can be smooth or notched. Their lateral surfaces (sides) are dominated by a dark brown lateral band with smooth or notched borders that are usually pale. The ventral (lower) surfaces range from pale-grey brown to yellow, and are usually unmarked, whilst the throat is typically lighter in colouration ranging from white-grey to grey-brown. Eye colour is typically brown-tan, sometimes slightly green. They usually possess a pale stripe on the forelimbs (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2022). Hypermelanstic/dark individuals have been observed from many localities.

Awarua morph: A relatively uniform colour variation that was initially discovered in Awarua Bay, Southland. They are characterised by their uniform dorsal (upper) surfaces, which are often dark brown, orange-brown, or olive-brown. The lateral surfaces (sides) are often a darker shade of the dorsal colouration. As with the striped morph, they exhibit a mid-dorsal stripe (often the same colour as the lateral surfaces), and on occasion pale dorsolateral stripes, although these are often hard to distinguish from their background colouration (Jewell 2022).

Tussock skinks (especially the striped morph) are difficult to differentiate from other members of the grass skink complex, however, Jewell (2022) notes that they can be differentiated from the southern grass skink (Oligosoma aff. polychroma Clade 5) by their head shape (long snout vs. blunt snout), and by colour/pattern (at least at their contact zone), with the southern grass skink being darker brown, having rough-edged stripes, and exhibiting fragmented or completely absent mid-dorsal, and outer-dorsal stripes.

Life expectancy

Largely unknown, but as with most of Aotearoa's small endemic skinks, their life expectancy is likely to be at least 10-20 years in the wild.

Distribution

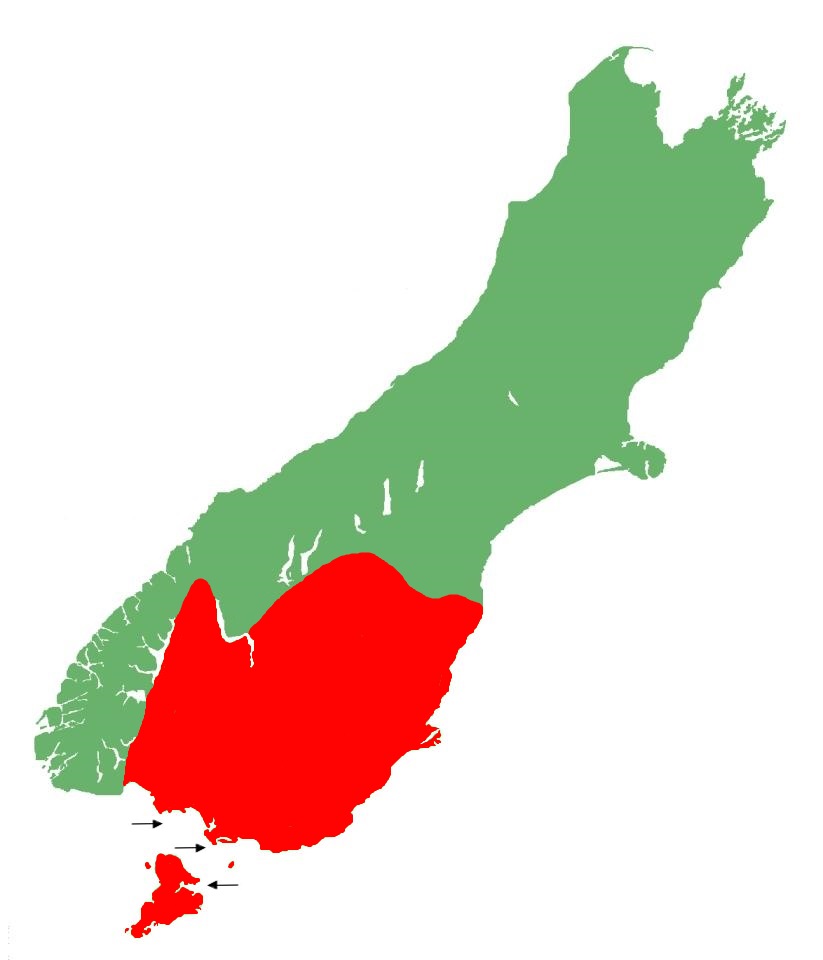

Being the southernmost member of the grass skink lineage, the tussock skink is found in the far south of the South Island, as well as the northern regions of Stewart Island. The species reaches its western limit at the far eastern edge of Fiordland National Park, and its northern limits are bounded by the Eglinton Valley, Lake Wakatipu, southern Crown Range, Pisa Range, Lindis Pass, St Bathans Range, Hawkdun and Ida Ranges, Danseys Pass, and the Kakanui Hills. Several populations are also known to occur on some of Stewart Island's outlying islands, as well as a number of islands in the Foveaux Strait, and Bluff Harbour (Jewell, 2022).

A population discovered in Milford Sound is likely to be the result of an accidental introduction.

Ecology and habitat

Tussock skinks are a very frequently seen species because they are diurnal, avid sun-baskers, and terrestrial. This species has been recorded in densities as high as 4000 per hectare (Wilson et al. 2017). Tussock skinks inhabit a range of habitats from sea level, up to 1,800 m (a.s.l) including coastal dunes, wetlands, grassland, shrublands, rocky shrubland/herbfield, screes, tussock, stony river beds and even cities.

Social structure

Unknown.

Breeding biology

This species reproduces annually and is mature at about 3 years old. Mating likely takes place around March, with 3-6 offspring born in the summer months (November-February) (van Winkel et al. 2018).

Diet

Tussock skinks are primarily insectivorous, feeding on small arachnids, beetles, and other invertebrates, but are also known to take advantage of the fruit and nectar of certain native plants when they are in season.

Disease

Tussock skinks are known hosts for the ectoparasitic mites Odontacarus lygosomae, and Ophionyssus scincorum, as well as the blood parasite Hepatozoon lygosomarum.

They are known hosts for the trematode Dolichosaccus leiolopismae, a species seemingly restricted to Aotearoa's reptile fauna (Allison & Blair, 1987).

Conservation strategy

Listed in the most recent threat classification as 'At Risk - Declining'. This species is not being actively managed. However, when land is developed/destroyed, this species is often salvaged and relocated to suitable habitat. This species is also present at a number of predator-resistant sanctuaries.

Interesting notes

This species has been observed occupying insect burrows.

Tussock skinks are members of a cryptic species complex which includes the northern grass skink (Oligosoma polychroma), Waiharakeke grass skink (Oligosoma aff. polychroma Clade 2), south Marlborough grass skink (Oligosoma aff. polychroma Clade 3), Canterbury grass skink (Oligosoma aff. polychroma Clade 4) and southern grass skink (Oligosoma aff. polychroma Clade 5). The various species are regionally distributed, similar in both appearance and habit, and were once regarded as a single highly variable species - the 'common skink'. There are currently no known morphological features to distinguish Tussock skinks from the other species within the complex.

References

Jewell, T. (2008). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland.

Jewell, T. (2022). Discovery of an abrupt contact zone supports recognition of a new species of grass skink in southern New Zealand. Jewell Publications, Occasional Publication #2022B.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M., Hitchmough, R. 2018. Reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand – a field guide. Auckland university press, Auckland New Zealand.