- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Laxa

Oligosoma laxa

Scree skink

Oligosoma laxa

(McCann, 1955)

Length: SVL up to 114 mm, with the tail being much longer than the body length

Weight: Up to at least 28 grams

Description

A beautiful and highly active species of large skink with a snout-vent-length (SVL) up to 114 mm. There are two main forms of scree skink. The Canterbury form and the Otago form. Mitochondrial DNA analyses indicate that the Otago form has introgressed with Otago skinks (Oligosoma otagense) at some point in the past, thus, their distinctiveness is uncertain (unpubl. data). The two main forms can be characterized as follows:

Canterbury

Dorsal surface typically drab pale or dark grey (sometimes with olive-green tint) with less pronounced black transverse bands and conspicuous dense speckles. In this form there is also sometimes a "gap" along the dorsolateral area, where black bands and dense speckles are absent. The lateral surfaces are similar to the dorsal surface, however the black bands are often absent. Instead, only dense black or brown speckles are present. In the Canterbury form, the transition from the dorsal basal colour to the ventral surface colour is less abrupt. Ventral surfaces similar to the lateral surfaces, but more uniform pale grey with few speckles and sometimes a pale orange hue.

Otago

Dorsal surface typically bright cream-yellow or tan (sometimes with olive-green tint), often with pronounced black transverse bands, and/or with black markings that protrude longitudinally. There is sometimes a series of conspicuous "gaps" along the dorsolateral area, where bold black bands periodically extend from the dorsal area to the lateral area. This results in what looks like a cream-yellow or tan dorsolateral stripe that is broken up or crenulated. Lateral surfaces similar to dorsal surfaces, with bold black bands or patterns, with a basal color that transitions to grey on the lower lateral surface. Ventral surfaces typically uniform pale grey with few speckles.

The Marlborough scree skink (Oligosoma aff. waimatense "Marlborough") has been identified as a separate species from the Canterbury scree skink, and is similar in appearance to the Otago form of this species.

Life expectancy

Upper limit unknown. However, it is probable that this species can live over 20 years.

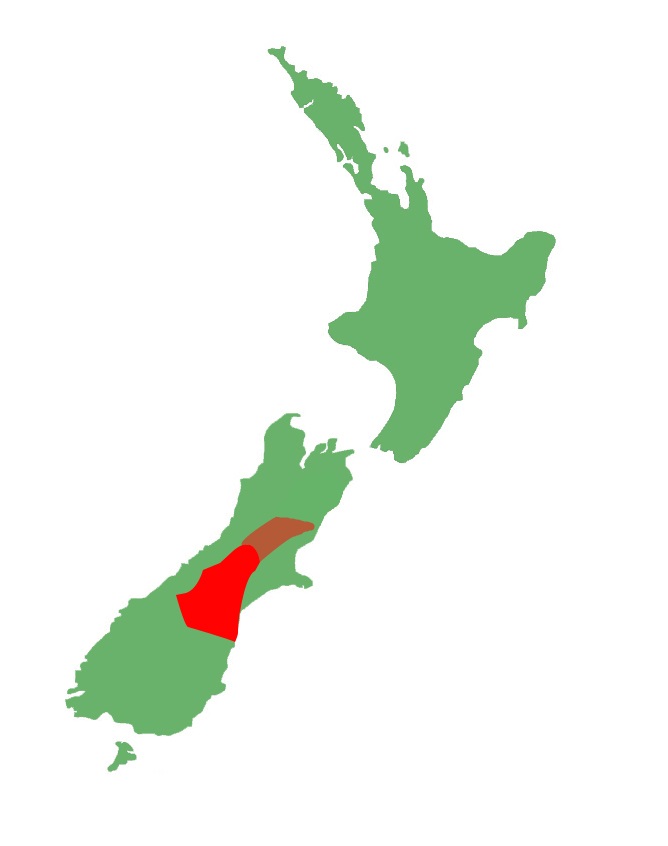

Distribution

Canterbury form

South-Mid Canterbury, Lake Benmore, Grampian Mountains, Dalgety Range, Two Thumb Range, Rangitata Gorge, Lake Heron, and Lake Coleridge.

Otago form

From Waitaki/lower Pukake southwards including the Dunstan Range, Ida Range and Saint Bathans Range in north Otago. May also have existed on Black Jacks Island in Lake Benmore.

Ecology and habitat

Scree skinks are diurnal, saxicolous, and avidly heliothermic. They are renowned for being highly active and mobile, with a maximum recorded home range size of 950 metres squared (Lettink and Monks, 2019). Scree skinks occur in both the lowlands and subalpine environments. They typically inhabit dry rocky areas with suitable refugia (their large size renders them more vulnerable to predators). These include boulderfields, screes, tallus, stoney river terraces and banks, rocky shrubland, and rocky bluffs.

Social structure

Unknown.

Breeding biology

Largely unknown, however, scree skinks may breed annually or biennially. Reproductive maturity is thought to be a minimum of 4-5 years of age (Lettink and Monks, 2019).

Diet

Invertebrates, smaller lizards (possibly including conspecifics), and native fruits.

Disease

Unknown.

Conservation strategy

Scree skinks are highly vulnerable to mammalian predation, partly because of their large size. Consequently, they only exist in a few areas in lowland habitat (compared to what their former extent would likely have been), and are more common and widespread at higher altitudes. However, when considering the decline of other mainland lizard populations, including other scree skink populations, it is probable this species is declining as a whole (Lettink and Monks 2019). A decade-long study by Lettink and Monks (2009) indicated that severe flooding and weather events may be a serious threat to scree skink populations. Following a severe weather event, a decline of 84% was observed in one scree skink population. This population gradually recovered after approximately 8.5 years unmanaged (Lettink and Monks 2019).

The authors of this comprehensive study made several highly useful conservation recommendations. Firstly, they suggested that monitoring at their study site continue, as studying a flood-prone population of scree skinks is highly valuable in the context of climate change. They also suggested that other scree skink populations be monitored long-term (e.g. 10 years) in scree systems, as their study site is fairly atypical of the species usual habitat. They also recommended that wilding conifers and other exotic trees should be controlled at scree skink sites, as shading out of habitat is thought to be a possible threat to scree skinks (Whitaker 2008; ML unpbl. data).

Interesting notes

Scree skinks are closely related to Otago skinks (Oligosoma otagense). Wild scree skinks in the Otago area show introgression with Otago skinks, and Marlborough scree skinks (Oligosoma aff. waimatense "Marlborough") have also been known to inadvertently hybridise with Otago skinks in captivity.

During research into the scree skink complex, Tony Jewell came across a holotype of a species referred to as Mocoa laxa, which had been relegated to a synonym of the grand skink (O. grande) for over a century. However, he noted that the description given to this specimen was more in line with the appearance of a scree skink. After the acquisition of a photo series from the British Museum of Natural History, it became apparent that the specimen in question was undoubtedly a scree skink from the southern extent of their range. As such this may require a correction to the species name from Oligosoma waimatense to O. laxa in future (Jewell, 2023).

References

Jewell, T. (2023). Oligosoma laxa (Hutton 1872): an overlooked name for the New Zealand scree skink (Reptilia: Scincidae). Jewell Publications, Occasional Publication #2023A.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

Whitaker T 2008. Conservation of lizards in Canterbury Conservancy. Canterbury Series 308. Christchurch, Department of Conservation.