- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Aeneum

Oligosoma aeneum

Copper skink

Oligosoma aeneum

(Gerard, 1857)

Length: SVL up to 76mm, with the tail being equal to or slightly longer than the body.

Weight: 5 grams

Description

The copper skink is a small, and often beautifully marked lizard that occurs throughout the North Island from around Kaitaia through to Wellington. For many of us (especially in the North Island) this will be the first native skink that we come across, often being found under garden debris/rubbish, or being brought into the house by the cat.

In general, the copper skink is characterised by its reddish to dark-brown dorsal colouration, which may be uniform or have scattered light and/or dark flecks. A bright copper-coloured stripe - the characteristic it is named for - is often easily observed along the boundary between its dorsal (upper), and lateral surfaces (sides). This feature often extends from just behind the eye and terminates on the tail, but may break up halfway down the body. In some individuals, this copper stripe is bordered below by a black stripe (broken, or unbroken), which may contain white flecking. Some individuals may also have a thin, black mid-dorsal stripe, but more often this is broken or completely absent.

The lateral surfaces are much the same as those of the dorsal, with the light or dark flecking, but may also take on a more reddish tinge.

The ventral (lower) colouration ranges from uniform cream to bright yellow, and yellowish green, although often become orange around the base of the tail. The throat is paler than the belly (usually white) and has heavy black spotting. An alternating black and white denticulate (tooth-like) pattern surrounds the mouth.

May be mistaken for the ornate skink (Oligosoma ornatum) with which they often coexist. However, ornate skinks are often much larger and have large pale cream/silver blotching on the dorsal surfaces (particularly on the tail), have larger external ear holes, and a large cream/white teardrop marking edged with black. In comparison, copper skinks are smaller, lack the cream/silver blotching pattern, have smaller external ear holes, and have a black and white denticulate pattern around the mouth, without the large teardrop marking.

Copper skinks may also be mistaken for the introduced plague/rainbow skink (Lampropholis delicata). However, in general, rainbow skinks can be differentiated from coppers by their more slender body, longer tail, gregarious nature, and their propensity to actively forage and sun-bask in urban gardens. In comparison, the native copper skink is rarely observed moving about and is generally solitary in nature. An additional feature which helps to distinguish the rainbow skinks from native skinks is the presence of a single frontoparietal scale across the top of the head (vs two frontoparietal scales in NZ skink species), although this can be quite hard to observe unless the animal is in hand.

Life expectancy

Largely unknown, but as with most of Aotearoa's small endemic skinks it is likely that their life expectancy is around 10-20 years in the wild.

Distribution

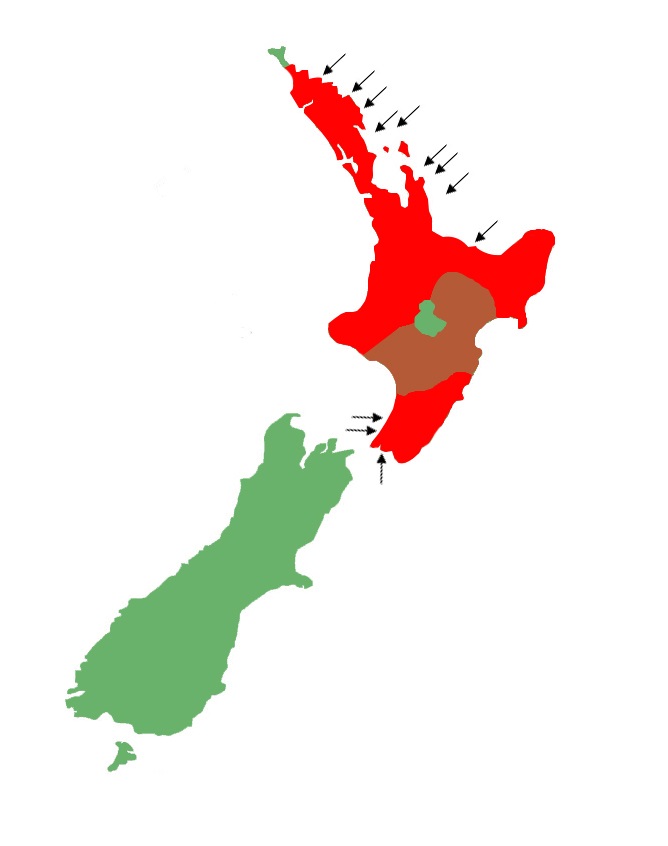

Copper skinks are the most commonly-sighted native skink in the North Island, they are widespread from just south of the Aupōuri Peninsula through to Wellington.

Ecology and habitat

A secretive species which rarely emerges from cover. Copper skinks are cathemeral in nature (active both day and night when conditions are suitable), but are fairly cryptic, remaining at the edge of cover, and hunting amongst dense undergrowth, or deep substrate.

Copper skinks inhabit areas with good ground cover in open and shaded areas of forests. In coastal areas, copper skinks can be found close to the high tide line. Copper skinks are also found in urban areas, most commonly found in thick-rank grass, compost heaps, or under rocks, logs and other debris.

Social structure

The copper skink is mainly solitary, maintaining a fairly small home range. However, several individuals can occasionally be found sharing the same retreat.

Breeding biology

Mating takes place in spring; copper skinks are ovoviviparous with females giving birth to 3-7 live offspring in January/February.

Diet

Small invertebrates; insects such as beetles, spiders, and mites.

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a clear determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The copper skink, as with many of our other Oligosoma species, is likely to be a host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematodes in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon poicilandri), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. Similarly, as with most ex-Cyclodina skinks they are unlikely to harbour large numbers of ectoparasitic mites in the wild.

Conservation strategy

Historically this species was considered 'Not Threatened', however, in light of the development of their primary habitat and threats from exotic reptiles, the most recent DOC classification has moved them to the ‘At Risk - Declining’ category.

Although not proven, it has been suggested that the introduced plague/rainbow skink (Lampropholis delicata) may outcompete this species in certain habitat types e.g. small isolated urban gardens. This along with the development of urban/suburban areas (particularly in Auckland) has resulted in this species' relative rareness in these habitats.

Interesting notes

The specific name 'aeneum' derives from the Latin word 'aenea' (meaning bronze/copper) and references the copper-coloured dorso-lateral stripes that are typical of this species.

The copper skink sits within clade 3 (the copper skink complex) of the Oligosoma genus, with the slight skink and Hardy's skink being its closest relatives within the group.

References

Gill, B., & Whitaker, T. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers.

McCallum, J. (1980). Reptiles of the northern Mokohinau Group. Tane, 26, 53-59.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1981). Reptiles of Cuvier Island. Tane, 27, 17-22.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1982). Reptiles of Little Barrier Island. Tane, 28, 21-27.

McCallum, J., & Hitchmough, R. A. (1982). Lizards of Rakitu (Arid) Island. Tane, 28, 135-136.

Towns, D. R. (1971). The lizards of Whale Island. Tane, 17, 61-65.

Towns, D. R. (1972). The reptiles of Red Mercury Island. Tane, 18, 95-105.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

Copper skink in Pohutukawa leaf litter (Tiritiri Matangi Island, Hauraki Gulf). © Nick Harker