- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Ornatum

Oligosoma ornatum

Ornate skink

Oligosoma ornatum

(Gray, 1843)

Length: SVL up to 94mm, with the tail being equal to or slightly longer than the body length

Weight: up to 13.9 grams

Description

The intricately patterned ornate skink is the most widespread reptile in the North Island, occurring from Manawatāwhi / the Three Kings Islands through to Wellington. Although they are widely distributed, ornate skinks are fairly large, and aggressive leading to a higher susceptibility to predation from mammals when compared to some of our other small skinks (e.g., copper skinks), and as such are much more sparse.

In general, ornate skinks are robust with a deep set head and short, blunt snout. The dorsal (upper) surfaces are light tan through to a very dark brown/almost black. Individuals usually have a dark 'wavy' edged stripe extending from the nostril to above the eye, and along the edge of the dorsum/flanks, often breaking up midway between the fore and hind limbs. Large pale blotches are seen along the top and sides of the tail, which often extend onto the back. In some individuals the tail may be flushed with red/orange. Ventral (lower) surface yellowish, either unspotted, partially or wholly spotted with black; some individuals have vivid reddish orange colouration. Head sports a ‘tear-drop’ below each eye (white or yellowish edged with black). Tail is thick at the base and tapers abruptly. Females are generally larger than males, with males rarely exceeding 70mm SVL, whereas females will often exceed 75mm SVL. Individuals have: between 15-23 lamallae on each toe; 28-34 mid body scales; 60-79 ventral scale rows.

Ornate skinks may be confused with Whitaker’s skink (Oligosoma whitakeri), but can be differentiated by having less ventral scale rows (60-79 vs 84-99). Similar to Hauraki skinks (Oligosoma oliveri) and Coromandel skinks (Oligosoma pachysomaticum) but can be differentiated by have less extensive black markings on the neck area.

Often confused with the more-common copper skink (Oligosoma aeneum), but can be distinguished by the presence of a tear-drop pattern under the eye (versus denticulate patterning in copper skinks), and proportionately larger ear-hole.

Life expectancy

Largely unknown, but as with most of Aotearoa's small endemic skinks, their life expectancy is likely around 10-20 years in the wild.

Distribution

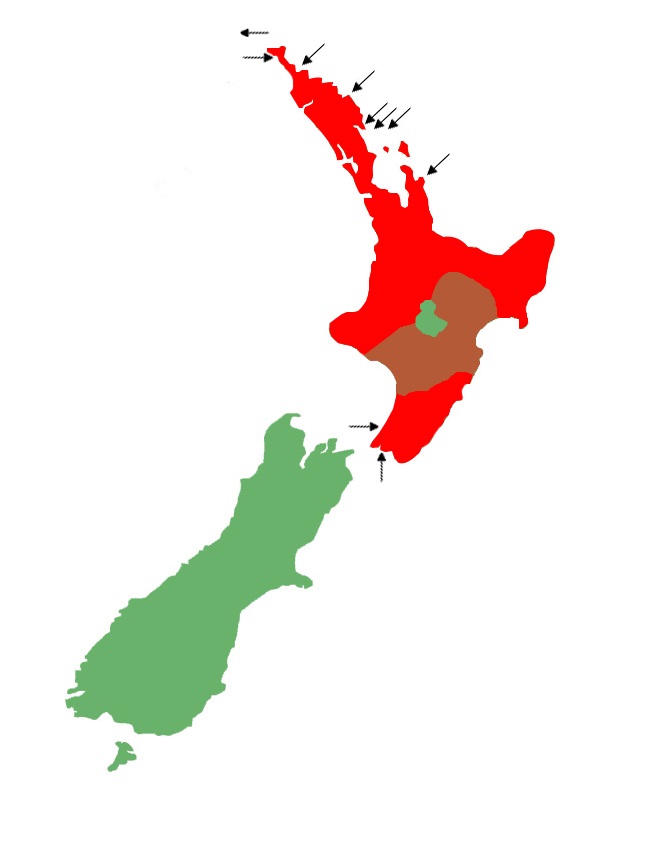

Ornate skinks are the most widespread skink species in the North Island, occurring from Manawatāwhi / the Three Kings Islands at the northern tip of the Aupōuri Peninsula through to Wellington. Although they are widespread, they are generally sparse, with robust populations typically being restricted to islands or areas with good pest control.

Ecology and habitat

A secretive species which rarely emerges from cover. Ornate skinks are cathemeral in nature (active both day and night when conditions are suitable), but are fairly cryptic, remaining at the edge of cover, and hunting amongst dense undergrowth, or deep substrate.

Ornate skinks inhabit forested areas, shrubland and heavily vegetated coastlines; they are often found amongst leaf litter, in dense low foliage, thick rank grass and under rocks or logs, and are known to occupy small burrows (which may be excavated by them, large invertebrates, or other skinks).

Social structure

Ornate skinks are solitary with adults being quite aggressive. Adults will not co-habit, however, it appears that they will tolerate their own young with large females being observed occupying the same refuge as 2-3 young (N. Harker, personal communication, December 1, 2016).

Breeding biology

Ornate skinks are ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young in January/February. It appears they may be able to have up to 8 offspring in a single clutch; with 2-4 large ova in each ovary. The average size for neonates is 25.5mm SVL. Males reach maturity between 15-16 months and females between 19-20 months.

Diet

The ornate skink is primarily insectivorous, feeding on small arachnids, beetles, and other invertebrates, but is also known to take advantage of the fruit and nectar of certain native plants when they are in season.

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a clear determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The ornate skink, as with many of our other Oligosoma species, is likely to be a host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematodes in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon poicilandri), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. Similarly, as with most ex-Cyclodina skinks they are unlikely to harbour large numbers of ectoparasitic mites in the wild, although they are a recorded host for one species in the Ophionyssus genus.

Conservation strategy

DOC classify ornate skink as ‘At risk - Declining’ with a total area of occupancy >10,000 ha (100km2), but a predicted decline of 10-70%. The species were included in DOC’s Cyclodina spp. skink recovery plan 1999 - 2004.

Interesting notes

At one time it was thought that the ornate skinks on Manawatāwhi / the Three Kings Island (often referred to as the ‘Manawha’ skink) were a distinct species. However, genetic research has since shown that the population was not genetically divergent from other Oligosoma ornatum populations in Northland.

Jewell (2022) suggested that populations of ornate skink on Northland's outlying islands (Manawatāwhi / the Three Kings Island, etc.) are a distinct subspecies, and gave them the scientific name Oligosoma ornatum longirostrum in reference to their elongated snout.

The ornate skink, along with its sister taxa (the Aorangi skink) sit within clade 4 (the teardrop skink complex) of the Oligosoma genus, being sister to the rest of the ornate skink complex (e.g. marbled, Whitaker's, Hauraki skink etc.). The Falla's skink, robust skink and Mcgregor's skink are also members of this clade but diverged much earlier.

References

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Hitchmough, R. A. (1977). The lizards of the Moturoa Island Group. Tane, 23, 37-46.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers.

Jewell, T. (2022). A new islandic subspecies of Oligosoma ornatum (Gray) in the Far North. Jewell Publications, Occasional Publication #2022A.

McCallum, J. (1981). Reptiles of the North Cape region, New Zealand. Tane, 27, 152-157.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1982). Reptiles of Little Barrier Island. Tane, 28, 21-27.

McCallum, J., & Hitchmough, R. A. (1982). Lizards of Rakitu (Arid) Island. Tane, 28, 135-136.

Towns, D. R. (1972). The reptiles of Red Mercury Island. Tane, 18, 95-105.

Towns, D. R., & Hayward, B. W. (1973). Reptiles of the Aldermen Islands. Tane, 19, 93-102.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.